Early Norwegian oil history

In 1889, Standard Oil established itself with its first office in Scandinavia. The company needed provision for its kerosene products and Scandinavia needed kerosene. Standard Oil was willing to use an aggressive marketing strategy to achieve its goal of taking over 85 to 90 percent of the Scandinavian market. An important part of the strategy was cooperation with local investors who knew the language, culture, legislation and had the same aggressive approach to business conduct.

Per Skarung – Company Historian Esso Norge a.s

Standard Oil grew out of the chaos surrounding the first oil discoveries in the United States between 1859 and 1870. The business started early even though the company was formally formed only in 1882. Standard Oil acquired control over sales of petroleum products in the United States before the company turned to the outside world. Before I tell the story of when Standard Oil secured a dominant position in the Scandinavian market, I will describe the start of the company in the USA and the strategy for further growth.

Standard Oil

In 1855, 16-year-old John D. Rockefeller moved from simple circumstances to the city of Cleveland in Ohio to become a businessman. He eventually got employment as an accounting officer and handyman at a trading company that ran a wide range of activities in the city and the surrounding rural districts. The first oil was found in 1859 in Titusville near Cleveland. Extraction of oil immediately proved to be an interesting business area, mainly as kerosene for lamps. Rockefeller quickly realized that the product offered unimaginable possibilities and already in 1862 invested in a small refinery.

He quickly learned that the oil industry was the "Wild West" of the time and badly needed more professional actors. Prices could fluctuate from 10 cents to 8 dollars a barrel, based on the current supply of products. The biggest problem, however, was the highly variable and sometimes dangerous quality of the products. It is estimated that between 6,000 and 8,000 Americans were killed by exploding kerosene lamps annually in the early days. Rockefeller's wife, Laura, was badly burned while lighting a lamp with dangerous kerosene.

In 1865, together with his partner Sam Andrews, he bought Ohio's, and the world's, then largest refinery. Andrews was perhaps the world's foremost expert on mineral oil refining. The company was named Rockefeller & Andrews.

The business idea was that all oil sold from the company should maintain publicly defined qualities. In this way, customers would know how the kerosene behaved when they lit the lamp. The kerosene should not smell, not soot the lamp glass, have the same ignition point every time the lamps were lit, give an almost white light and not be explosive. To achieve the goal, Rockefeller and Andrews wanted to build refineries of sufficient quality and equip all with laboratories that continuously checked the products. After 1882, the business idea was embodied in the name "Standard Oil".

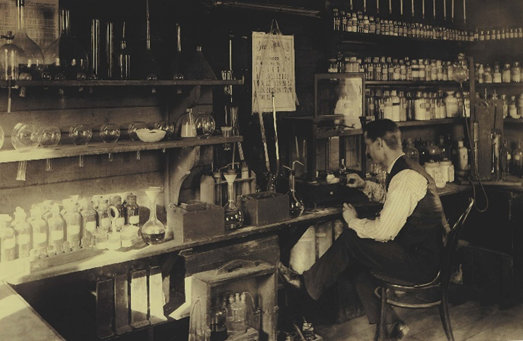

Typical laboratory from a refinery owned by Standard Oil.

Typical laboratory from a refinery owned by Standard Oil.

Photo: ExxonMobil Historical Collection at the University of Texas at Austin.

Initially, Rockefeller was not interested in producing oil himself, since there was more than sufficient supply of oil. This philosophy had to change when uncontrolled drilling destroyed reservoir properties. A lack of cost control threatened otherwise good companies with bankruptcy, and Standard Oil needed stable high deliveries. The company chose a strategy where it gradually took over the entire chain from exploration, via production to refining and transport and sale of the final products. The final products had distinctive packaging, often in light blue with simple symbols such as tiger, elephant and the like. This was necessary in a market where many were illiterate, or the sales took place in languages other than English.

The company maintained strict cost control and the management became, in some cases, extremely unpopular. All investments over USD 2,500 in the subsidiaries had to be approved by the executive board. Rockefeller went through the production processes in detail and, among other things, reduced the number of drops for sealing kerosene jugs, from 40 to 39.

His business model was that the profit lay in high volume at low prices. With this model, Standard Oil profited well regardless of economic conditions and eventually took almost total control of oil operations in the United States. When the company entered markets it should have dominance with an 85-90 percent market share. The last bit was given to small businesses to avoid charges of trust activity.

Competitors were first offered cooperation and "membership" in Standard Oil. Rockefeller liked to show the company's profitability compared to the company they wanted to take over, and usually offered very good terms to join Standard Oil. Those who still resisted takeover were bought, outcompeted or pressured by any means available. This could take place, among other things, through the acquisition of barrels, tanks, railway capacity, blockade of transport possibilities, or important deliveries, acquisition of customers, processing of shareholders and banks.

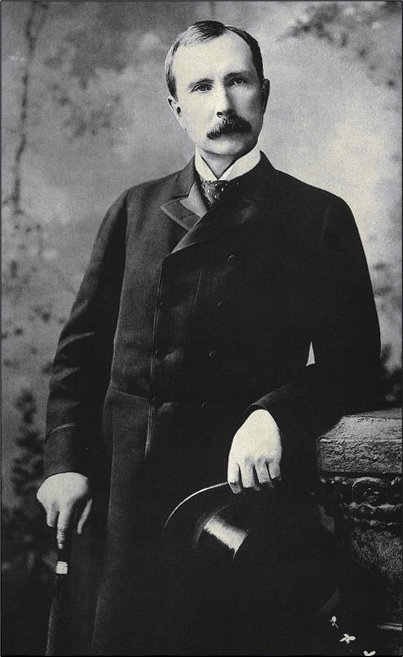

John D. Rockefeller, 1884.

John D. Rockefeller, 1884.

The possibilities for blocking competitors were endless. Standard Oil preferred to let acquired companies retain their names and outwardly continue as before. Local investors and part-owners had a strong motivation to succeed, and former owners were happy to continue so that Standard Oil avoided accusations of trust activity.

At the same time, Rockefeller himself, and the company, were concerned with charity. Rockefeller had started by financing the escape of an elderly slave couple via the so-called "Freedom Trains" with the savings from his first year as a businessman, aged 17. This involvement continued via the Baptist church he belonged to, to extensive philanthropic activities. Neither Rockefeller nor the company saw any contradiction between "tough" business practices bordering on the illegal and charitable work often in conjunction with churches. 1

None of the Scandinavian countries were in themselves large enough to be interesting for Standard Oil. But Denmark, Sweden and Norway together were an interesting market.

The Danish Petroleums Aktieselskap (DdPA)

The Danish market was from approx. 1860 supplied via Hamburg, to individual traders and wholesalers around Denmark. The peace after the Danish-German war in 1864 made trade via Hamburg less attractive.

Wholesaler Jørgen Jensen in Copenhagen traded, among other things, in kerosene and after some time started direct imports from the USA. The company also sold to Norway and Sweden from Copenhagen. It was not until 1876 that Rudolf Wulff formed a company mainly aimed at buying and selling kerosene. It gradually became clear that strongly changing prices made it difficult to establish a solid business. He contacted Jørgen Jensen and wholesaler Johs Holm and had a binding price agreement drawn up in 1887. It quickly turned out not to work well enough.

In November 1888, the three decided to establish Det danske Petroleums Aktieselskap, with a formal foundation date of 1889. The company aimed to import kerosene, candle wax, lubricating oil and the like from Standard Oil, mainly to Denmark. But they also saw that Copenhagen was strategically located as an import port for the rest of Scandinavia. The products were imported in barrels by sailing ship. Communication with the exporter in the USA took place easily and quickly via telegram.

The shipping of the products was risky and impossible to calculate in time, as the sailing ships could be several months late. To reduce the risk of shipwrecks, the company needed expensive insurance and storage facilities. Not least the company needed partners who could share risks and expenses. DdPA had one million Danish kroner in share capital at the start. It was twice the starting capital of the Norwegian companies. This very solid capital base made it possible to acquire warehouse space with wharves, tank facilities, bottling plant, barrel workshop, office, workers' housing and necessary facilities on Refshaleø just outside the harbor in Copenhagen. The location was perfect since the site became an industrial center with the shipyard Burmeister & Wein as a large neighbour. The capital was also needed to order cargoes that could run into several hundred thousand Danish kroner per sailing trip from the USA to Copenhagen.

Due to the fire hazard, Danish legislation in 1892 prohibited the bottling of kerosene by local traders. This gave the company a great advantage with its own bottling plant and distribution of bottles and smaller tin cans. Tank facilities and bottling plants were quickly built in a number of Danish ports and later also at major railway stations. The collaboration with Standard Oil was formalized in a separate agreement on 22 March 1892, and Standard Oil took over approx. 1/3 of the share capital in DdPA.

DdPA had already looked for partners outside Denmark before the agreement with Standard Oil based on the network Jørgen Jensen had in Scandinavia. In November 1890, the company helped found Vestlandske Petroleumscompagnie with sales from Lista to Vadsø. In 1892 they again founded Østlandske Petroleumscompagnie with sales from Kristiansand to Gothenburg. In Sweden, DdPA established several smaller companies in collaboration with Swedish trading companies. These later grew together into three companies where Vestkustens Petroleums Aktieselskap became significant for Norway. 2

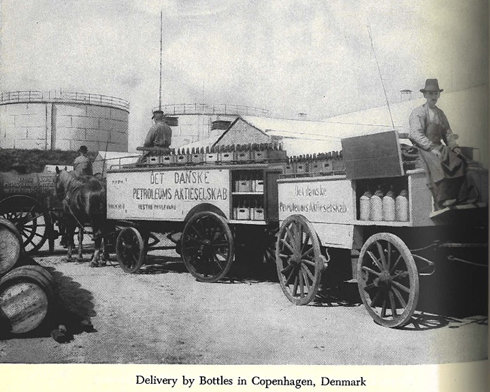

Deploying kerosene in Copenhagen before the year 1900.

Deploying kerosene in Copenhagen before the year 1900.

The Norwegian companies are formed

The import of kerosene into Norway had been hampered by a long series of taxes. These were gradually reduced and finally discontinued when the luxury tax on kerosene was abolished by the government of Johannes Steen, from the Radikale Venstre, in 1890/91. Oil lamps were no longer considered a luxury for the few. The fee was almost half of the price, and thus the profit opportunities on importing kerosene were significantly improved.

Vestlandske Petroleumscompagnie (VPC) was founded in November 1890 by a group of twelve investors based in Bergen. The well-known Bergen families Mohr, Brun and Irgens were involved from the start, together with Det danske Petroleums Aktieselskap. The investors committed themselves to an amount in share capital as a guarantee for the bank, but only paid in one twelfth of the formal capital. The Danish party owned approx. a third of the company and was responsible for the deliveries of products.

The company built a reception and warehouse in Skålevik just outside Bergen. The danger of fire and explosion made it necessary to keep a good distance from the city centre. The first load of 11,498 barrels (almost two million litres) arrived in June 1891 from Copenhagen. The company was an immediate success and supplied the entire coast, with warehouses in Stavanger, Karmøy, Haugesund, Ålesund, Kristiansund, Trondheim, Bodø, Harstad, Tromsø and Hammerfest. The shareholders received an average of approx. 20 per cent return on their formally "paid-in" share capital, and several amassed large fortunes. 3

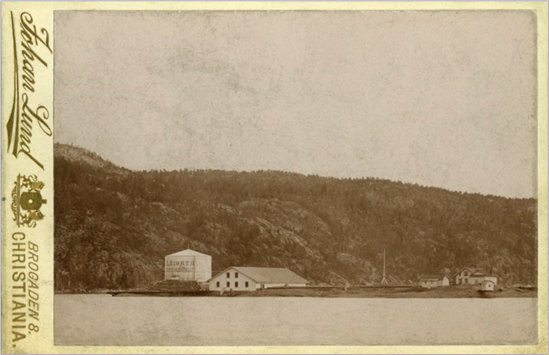

Skålevik around 1910.

Skålevik around 1910.

The company's first iron tanker "Conrad Mohr" is at the quay.

Østlandske Petroleumscompagnie (ØPC) was formally formed in May 1893. Adam Hiorth was one of the pioneers in the Norwegian textile industry with spinning mills in Nydalen. In 1859, he invested part of the capital in a trading house that invested heavily in the import and sale of petroleum products, mainly kerosene for lamps. In other words, the company was well established under the management of Adam Hiorth's son, Christian Hiorth, when it was invited to participate in the collaboration with Det danske Petroleums Aktieselskap and Vestlandske Petroleumscompagnie in 1892. Østlandske Petroleumscompagnie established itself with an office in Adam Hiorth's premises in Christiania. 4

The main owners were Christian Hiorth and managing director and co-owner of the company A. Hiorth, Andreas Lind, together with investors with smaller holdings, including Det danske Petroleums Aktieselskap. DdPA received approx. one third of the shares and a permanent seat on the board. The company sold products from Standard Oil delivered via the Danish company. The operation was a direct continuation of the operation in A. Hiorth, with the same customer base. A couple of the investors had their own imports of kerosene which were transferred to ØPC with their inventories.

The company employed a manager and office manager and quickly built up a small administration. There were two top levels; the small board consisted of Andreas Lind, Christian Hiorth and one of the investors, and the large board with all shareholders including Det danske Petroleums Aktieselskap. The small management had weekly meetings and was directly involved in the management. The large board had two meetings a year. It controlled the price policy and the cooperation between the national companies. The large board of directors also ensured the payment of dividends - return on the shares. Eventually, they gained cross-ownership by buying shares in each other's companies. The share capital increased several times in all the companies to finance investments and increase the "crisis fund". There was also cooperation on the purchase and operation of ships for shipping along the coast. A Swedish inspector checked that the companies did not compete against each other on price. 5

Adam Hiorth's plant from 1890 at Landsteilene with tank, warehouse,

Adam Hiorth's plant from 1890 at Landsteilene with tank, warehouse,

workers' housing and outdo, conveniently located above the sea.

ØPC bought Hiorth's plant at Steilene and expanded with a new tank during 1893, to approx. NOK 30,000. The company rented office space in Hiorth's business yard on the corner of Skippergata and Prinsens gate in Oslo. Here you could also use a stable, carriage shed, cellar, boys' room, weighing shed and hayloft at a price of NOK 3,500 per year. 10 to 12 horses with carriages and harness were bought. ØPC bought land and berth space in Bispevika, so that the company got a large berth at Bispekaia with a gate towards Bispegata just below the railway station. The plot was fenced, and in December 1893 warehouses and stables were built with space for 40 horses, carriages, harness and added grooms in full time. In total, the area was more than 5,000 m2 at a purchase cost of NOK 58,500. The plot was expanded several times by the purchase of neighboring plots. Today, the Munch Museum is located on this site.

ØPC and VPC sold the qualities Snowflake (Crystal white) as the most expensive product, Prime and Water White as number two, Standard White as number three and Russian oil as number four. The qualities followed the American standards, as defined by Standard Oil. The prices were around 10 to 19 øre per kilo and varied quite a lot from delivery to delivery. The cheap Russian oil came from Brødrene Nobel and was delivered by boat directly to the facility at Steilene. The sales overviews show that the most expensive qualities had the highest volume. The Russian kerosene was clearly the cheapest, but with the lowest sales volume. 6

All imports from the USA came from Standard Oil and were coordinated and physically arranged by the office in Copenhagen. It was an indirect route, but it gave flexibility and security as Copenhagen could supply Norway, if there were problems with deliveries from its own warehouse. Cargo insurance was shared between all the companies, and the Norwegian volume was not large enough to cover the entire ship's cargo.

The small management decided the orders and had to assess demand half a year ahead. But Copenhagen's priorities could also mean that it received far less than the ordered volume (for example, 7,000 barrels delivered against 25,000 barrels ordered in March 1898). In some cases, the companies could exchange deliveries if some had a shortage of products or qualities. Both VPC and ØPC experienced that the supplies were uncertain, since the Danish company would always prioritize the domestic market first. Nevertheless, they never attempted to break away from the collaboration with DdPA.

ØPC sold its products along the coast from Kristiansand to Gothenburg via a network of wholesalers, trading points and its own facilities; Kristiansand, Drammen, Fredrikstad. The inland Swedish west coast was a good market with several large cities. The sales were mostly small volumes distributed among many recipients, but the company also had some large customers. The Norwegian fire service, Christiania Lysværk, Norges Statsbaner and the navy at the main base in Horten, Karljohansvern, bought large quantities of the best quality every year.

Transport inland was limited by poor roads and the weight of the barrels. The company used trains and horse and cart transport where possible. In this way, a network of customers in the inland eastern region was gradually established. Transport was initially in barrels, and the end user had to buy kerosene in its own packaging such as bottles, milk pails and the like. The growth in volume required a significant expansion of the facilities at Steilene.

The cliffs at Nesodden became Norway's oil centre

Steilene was a group of five small islands, almost islets, off Nesodden in the approach to Christiania. ØPC bought the two islands closest to land, Land-Steilene and Persteilene. The cliffs, less than 100 meters to the north, remained unused for the time being. The two islands were connected by a bridge and later an embankment. Kvaerner Brug led by engineer Wohl built a new tank every year and was responsible for the other extensions. By 1895, the storage capacity had reached more than 100,000 barrels (16 million litres). The wharves were built out, including with cranes for more efficient loading of the harbor barges that transported the products into Christiania. There were workers' quarters, a residence for the operations manager, a stone factory building for the production of jugs, a bottling plant, a bookmaker's workshop for the production and maintenance of barrels, a steam laundry for cleaning barrels, pipe streets, a large steam engine for operating the plant, a coal warehouse, a tool shed and a plant for electric light with 30 incandescent lamps.

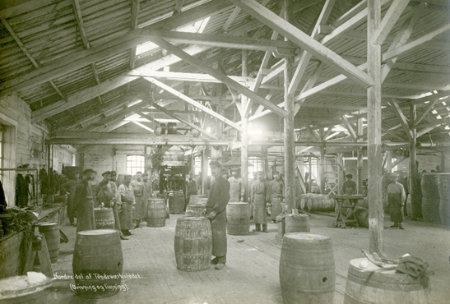

Books in the large production building at Persteilene

Books in the large production building at Persteilene

Some workers established themselves with families on the islands and on land just inside the Land-Steilene. Capacity problems arose in several areas. The production facility and the homes needed fresh water. It was not enough to collect rainwater in a cistern. ØPC bought a large area on land, on Nesodden, including two smaller aqueducts that supplied water via pipes to the islands. This plant was further expanded in modern times and to some extent still constitutes Nesodden's water supply.

The jug factory made kerosene jugs of five liters with corks and labels. These jugs were a revolution as they were easier to transport and enabled end users to purchase one or more jugs. The labels had a picture and color code that made it easy for customers to recognize their product. Empty jugs could be returned or used for later purchases directly from barrels and tanks.

Brewery at Landsteilene with tank, barrels, 5 liter jugs,

crane and the harbor barge "Glunten".

Brewery at Landsteilene with tank, barrels, 5 liter jugs,

crane and the harbor barge "Glunten".

Nesodden municipality had to provide a school for the children of the workers, and ØPC contributed funds to improve the school and the school road so that the children arrived fairly dry. Each year the church received a barrel of kerosene and NOK 50 for the priest.

The need for better transport capacity led to the contracting of a completely new ship, "Petrolea", from Fredrikstad Mekaniske Verksted. Stack drainage was in October 1894, and the ship received electric lighting and a steam boiler. "Petrolea" was immediately put into operation with transport along the coast from Gothenburg to Kristiansand. The ship was insured for NOK 35,000.

The company was so satisfied with Steilene that Christiania's press was invited along on a trip with "Petrolea" to Steilene. The press was very impressed and reported thoroughly to their readers. Good food and drink during the trip probably did not dampen the mood.

In 1897, the coal warehouse self-ignited and burned to the ground. In addition, the nearest houses and the nearest pier were damaged. The Christiania Fire Service could not help, and the crew on Steilene had to extinguish the fire by heroic efforts with buckets and wet sails. They received a generous reward for their efforts. The facility on land was not insured. ØPC responded by taking out solid insurance and rebuilding the facilities more solidly and modern than before. The company bought large parts of the island of Alvern to the south and developed it. All wharves became a prohibited area for anyone other than ØPC employees. 7

The operations manager at Steilene for many years, Alfred Andresen, was one of Nesodden's largest taxpayers and had a permanent seat on the municipal council. He went by the nickname "King of the Nose". 8

Conditions for the workers

There seems to have been a stable workforce in the administration and in leading positions on the wharf and Steilene. The company provided wages, partly significantly above average for similar positions. Dispatcher J. E. Oldenborg had a fixed salary, rising from NOK 8,000 to NOK 19,000 plus bonus, based on turnover and profit. This was 40-50 times more than the stipulated average salary for an ordinary servant, or worker on NOK 250 a year. Office manager Georg Kalleberg and accounting officer Henry Carlsen had NOK 3,000 in 1893. The rest of the administration, varying from 10 to 15 employees, all had well above average wages. There was only one woman employed in the company, Miss Berg. She seems to have had her entire career in ØPC, although it is not clear what duties she had. She received NOK 600 upon employment in 1894, and this was increased to NOK 1,200 six years later.

Those in charge of operations on the pier and Steilene, the shipmasters and foremen, were also paid very well, with salaries from 1,200 and upwards. The workers received regular average wages per day, week or month, depending on the employment contract. Everyone received Christmas bonuses of NOK 10 or NOK 5 depending on the family relationship, married or single. The company organized outings with sandwiches and drinks for employees with families on the company's boats a couple of times a year. When "Fram" and Fritjof Nansen returned from their stay in the Arctic in 1897, all the company's boats with employees in the cortege were decorated with flags. 9

In the administration, working hours were from 09:00 to 19:00 six days a week with a one-hour break. On the pier and Steilene, working hours were from 07:00 to 19:00 without a regulated break. Unlimited overtime without extra remuneration was expected, when there was a need for it. In practice, this meant that most of the accounting and paperwork on the pier took place late in the evening and at night. The foreman on the pier was observed at the office desk until long after midnight. There was no documented dissatisfaction among the employees in Christiania. On the contrary, it seems that well-being was good and the workers satisfied.

On the other hand, major problems with the workforce at Steilene were documented. It is possible that the isolated existence and distance from Christiania contributed to that. The operations manager and the foreman of the books complained about the work discipline a number of times. In 1897 things got so bad that they were given permission to dismiss all employees and replace them with more disciplined and hardworking people from Rogaland. It seems that the threat of importing Rogalanders was enough to calm the staff at Steilene, since further problems were not documented later. It may also have contributed that ØPC bought in as a part owner in Larvik Tønnefabrikk to ensure alternative access to barrels made of beech. 10

Only one serious case of irregularities is reported. Chief treasurer Henry Carlsen was exposed with significant embezzlement during several audits. He excused himself with unclear control of the pier and had a telephone installed for direct contact with the foreman there. During later audits, it turned out that large arrears were not due to a lack of contact, but to large personal consumption by the chief cashier. His brother stepped in and covered part of the loss with NOK 15,000 in exchange for the embezzlement not being reported. 11

There were no provisions on vacation or sick leave in Norway at this time. Holidays for the workers were unknown. The small board, on the other hand, granted ad hoc both sick leave with pay and holidays for individuals in higher positions, based on applications and recommendations. It seems that the top management (Oldenborg and Kalleberg) were at times heavily overworked and were regularly sent on holiday or extended stays for meetings with the other companies. But employees further down the ranks also received paid holidays and sanatorium stays in special cases.

Interior from the office of Vestlandske Petroleumscompagnie in Bergen.

Interior from the office of Vestlandske Petroleumscompagnie in Bergen.

The office managers were known for strict discipline in the offices. They had their own office at the back of the room, separated by a frosted glass wall. The office was otherwise equipped with high fixed desks and high stools. There was a bodega in the neighboring building in Christiania, and some people chose to eat there. In some cases, they could be quite tipsy when they returned. It is said in a memory that some fell asleep and fell to the floor with a distinct thud. Then it was important to be up again before the boss could get into the room to check the cause. It is also said that one of the employees was a good ski jumper and wanted to take part in the Holmenkollrennet. When he asked for permission to leave early on the Saturday the race was held, Kalleberg replied: "Have you no respect for the company?" He still got time off and won the Ladies' Cup. The ladies' trophy was awarded by a female jury to "the handsomest skier from Christiania" during the annual Holmenkoll race well into the 20th century. 12

The company had an early interest in charitable contributions. The church and perThe Estonians on Nesodden received, as mentioned, annual contributions in the form of money and kerosene. In addition, a number of orphanages and institutions for adults received generous contributions in the form of money and kerosene. This applied to the Seamen's Mission, the Deacon Home, the Indremission, Nesodden Sanatorium, Kampen Arbeidsstue, work homes for the deaf, old people's homes, school ships, collections for those in need and ad hoc gifts in the event of major accidents and others. The charity does not seem to have been affected by changing economic conditions.

Vestkustens Petroleums Aktieselskap

Swedish authorities placed restrictions on foreign companies' opportunities to sell kerosene, and the company in Sweden faced greater competition from the Nobel Brothers from 1896. The Scandinavian partners had to form Vestkustens Petroleums Aktieselskap (VPA) to control the trade in petroleum in south-west Sweden up to and including Värmland and Karlstad. ØPC had to hand over this market to VPA in return for them promising not to sell petroleum in Norway, and to keep the same prices as in Norway. This proved difficult as the freight costs on the Göta canal and Vänern had to be lower than transport in Norway. In periods, kerosene was cheaper in Gothenburg than in Christiania.

ØPC and VPA were mentioned in Norwegian newspapers as competitors. It does not seem that the hidden collaboration between the "petroleum companies" in Scandinavia was discovered either by the authorities or the press.13

The sales volume for ØPC decreased as a result of the creation of VPC, and this was noticeable for several years. ØPC became one of the shareholders in VPC and received a share of the company's profits each year. Another important point was that VPC made no attempt at competition against Norway. The carefully defined sales districts were respected. The Nobel brothers' opportunities for their own sales promotions in Norway were in reality neutralized by the cooperation between the companies led from Copenhagen.

The monopoly is attacked

23. In May 1893, ØPC received information that a foreign company, Pande Lundby Co, had formed a subsidiary company in Norway with NOK 700,000 in share capital. The small management immediately negotiated with them and got the competitor liquidated in exchange for the parent company being allowed to buy a share of the deliveries from Standard Oil for three years. ØPC took over the warehouse and business with turnover in Drammen for a very good price for the seller. But this was only a ripple in the water against the attack that came in 1897, with the formation of Det norske Petroleumscompagnie (DnP).

In March 1897, a consortium of investors formed Det norske Petroleumscompagnie and established a large modern plant on Storsteilene with two tanks, wharves, workers' housing and electric light within sight of ØPC's plant to the south. The directors of ØPC contacted the company and invited a collaboration. This was flatly rejected by DnP's management. The management then decided that the new company had to be fought with all means. A lawsuit was brought against the new company for unfair competition. They lost in the court in Christiania, and appealed to the Supreme Court with another loss. ØPC approached Nesodden municipality and wanted DnP blocked from Storsteilene.

In addition, children of the workers in DnP should not have access to the school partly financed by ØPC. Both demands were rejected by the municipality. Then ØPC demanded that the school children stay away from the road the company had built. They were allowed to walk on the side of the road if necessary. The company approached the priest at Nesodden and wanted him to exclude the workers in DnP from the church and communion. When the priest could not agree to it, in 1897 he lost both the allowance and the kerosene.

Landsteilene and Persteilene owned by ØPC and Storsteilene owned by Det norske Petroleumscompagnie

just behind, in 1898. DnP's two new tanks light up. One of two barrel mountains on the right in the picture.

The manager's residence, outbuildings and production building in brick with a powerful steam engine and pipe

still stands and is used by Nesodden Municipality. "Petrolea" in the foreground.

Landsteilene and Persteilene owned by ØPC and Storsteilene owned by Det norske Petroleumscompagnie

just behind, in 1898. DnP's two new tanks light up. One of two barrel mountains on the right in the picture.

The manager's residence, outbuildings and production building in brick with a powerful steam engine and pipe

still stands and is used by Nesodden Municipality. "Petrolea" in the foreground.

The Norwegian Petroleum Company had a very aggressive strategy and attacked the market from Fredrikstad to Stavanger with greatly reduced prices and direct personal inquiries to traders and wholesalers. ØPC responded by halving all product prices. ØPC attempted to buy up all available barrels in the area and demanded that Larvik Tønnefabrikk should not sell barrels to DnP. When the barrel factory did not follow this advice, the factory was acquired. All production of barrels thus went to ØPC. Dispatcher Oldenborg and office manager Kalleberg visited all customers in their network personally to discuss the customer relationship. No one was allowed to withdraw from concluded contracts, and no one was allowed to sell products from both suppliers. Customer relations continued on very favorable terms.

The Scandinavian network of "Standard Oil" companies was mobilized, and deliveries to the new company from the USA were blocked. Chairman and director of Det danske Petroleums Aktieselskap, Rudolf Wulf, approached the management of DnP to negotiate cooperation, or an amicable end to the competition. This was again refused. ØPC responded by cutting all product prices to 6 øre per litre. The price war was costly for ØPC, which more than halved profits in 1897. But there was still profit, and the charitable contributions outside the church at Nesodden continued as before. Dispatcher Oldenborg had his salary cut by approx. 60 per cent as a result of a fall in profits. The shareholders, on the other hand, took their standgive dividends without further discussion in the senior management.

The fronts were just as steep in 1898, and the mutual combat between the companies continued. The acquisition of oil barrels provided Steilene with a stock that exceeded 70,000 barrels. They were like small mountains, piled up clearly visible at the production plant. During the general meeting of the large management in July, it was decided to sell part of the site at Bispekaia in order to raise capital and come up with yet another negotiating solution to DnP.

Before these measures could be implemented, Det norske Petroleumscompangnie went bankrupt in August 1898. ØPC managed to obtain sufficient loans to raise NOK 300,000 in new capital. These were used to buy DnP with all assets at Storsteilene and the pier in Christiania. ØPC received the entire inventory, all sales contracts, empty barrels, houses, wagons, horses, sledges, seals, steam boilers and barges. The first action was to repaint the tanks at Storsteilene with ØPC's logo, clearly visible from land and sea. Foreman, machinist, two assistants and all workers at Storsteilene, a total of 67 people, kept their jobs with the same pay conditions. The entire management of DnP was dismissed with immediate effect effect. 14

This demonstration of power on the part of ØPC made the company dominant along the coast and in the inland eastern region for many years. The donation to Nesodden Church was increased to NOK 100, together with kerosene for lighting and heating. The school at Alvern was painted. Dispatcher J. E. Oldenborg had discovered that bonus-based pay was dangerous and switched to a fixed salary of NOK 15,000. In addition to these measures, the company continued as before and the shareholders in the senior management refused to reduce their dividends in order to reduce the debt the company had taken on. For many years they had a steady return of 20-25 per cent on their share capital. 15

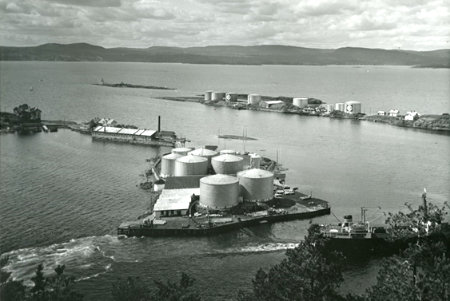

The steeps as they were developed around 1960.

The steeps as they were developed around 1960.

It was the Esso companies' main refueling facility

before Sjursøya and Ekebergåsen were built around 1965.

Literature and footnotes

The images with Norwegian motifs are taken from ExxonMobil's historical archive, the Norwegian Oil and Gas Archive, the National Archives Stavanger and the images from the USA and Denmark from ExxonMobil's historical collection at the University of Texas in Austin.

Values created over 100 years, Esso's anniversary book 1993.

1 The paragraph is a brief summary of the main points of Chernow, Ron. Titan, The life of John D. Rockefeller. Random House. New York. 1997 and Hidy, Ralph W. and Hidy, Muriel E. Pioneering in big business 1882 – 1911. Harper and Brothers. New York. 1955, and Sandvik, Pål Thonstad and Storli, Espen. "Standard Oil and monopoly capitalism's entry into Norway, 1890 – 1935", Historical Journal no. 3, University Press 2021.

2 The Danish Petroleums Aktieselskap's anniversary book from 1939, and Sandvik, Pål Thonstad and Storli, Espen. "Standard Oil and the rise of monopoly capitalism in Norway, 1890 – 1935", pp. 241ff.

3 Vestlandske Petroleumscompagnie's foundation minutes and board minutes December 1890 to 1907, ExxonMobil's historical archive, Norwegian Oil and Gas Archive, National Archives Stavanger.

4 Adam Hiorth, Norsk Biographical Lexicon, nbl.snl.no/Adam Hiorth, and ØPC foundation protocol 1893, Protocol and meeting minutes 1892-1960.

5 The Swedish Archives, Online exhibition on Westland and Eastland Petroleum Companies, 2018, and foundation protocol for ØPC.

6 Compilation of information from the minutes of the small board 1892 to 1901. Østlandske Petroleumscompanie Board minutes 1892 – 1905. The small board consisted of three people who met at least monthly and had ongoing control of the company's operations. The connection to Brd Nobel and the Russian oil was a legacy from A. Hiorth which was continued in understanding with the "mother company".

7 The information comes from the minutes of meetings in Den lille direksjon 1892 to 1901. Østlandske Petroleumscompanie Board minutes 1892 – 1905.

8 Tvedt, Nils. Steilene, 5 islands in the Oslofjord. Small book about Steilene's history, geology and flora published by Nesodden Municipality, Culture Department. 2009.

9 Salary, Christmas bonuses, ad hoc benefits are referred to in detail from the meetings of the Small Directorate.

10 Minutes from the small directorate on 16 March 1897.

11 Minutes from the small directorate on 21 October 1898, 1 July 1899 and 24 July 1900.

12 Memory from Erling Angell, treasurer at the office in Christiania from 1892 to 1924, ExxonMobil's historical archive, Norwegian Oil and Gas Archive, National Archives Stavanger. The companies were good at getting written memories from central employees who had a long tenure in the companies. These often provide personal experiences and sharp observations without

the official reports' filter.

13 Vestkustens Petroleumscompagnie is regularly mentioned in meeting minutes and protocols. The collaboration between the companies continued for many years largely problem-free where ØPC owned shares in the company. Only the pricing of products could create hazecushions. Østlandske Petroleumscompanie Management minutes 1892 – 1905.

14 Meeting minutes and minutes from 1897, 98 and 99 provide detailed information about the fight against DnP and the takeover in 1898/99.

15 Minutes from the Great Directorate, 28 July 1899.