Norway's first oil refinery was located in Mandal from 1862 to 1871

Mandal 1850 to 1875

Mandal took part in the general economic upswing in Norway after 1850, but to a more moderate extent than many other coastal towns such as Stavanger, Kristiansand and Arendal. Business life was varied, linked to shipping, lumber, sawmilling, trade, agriculture and for a period Norway's first oil refinery, 1862 to 1871. In 1850 the population was approx. 2,500, in 1855 2,719, in 1865 3,842 and finally in 1875 4,030. The population increased by in other words, about 40% in parallel with the establishment of the refinery and expansion in shipping.

Kleven served as Mandal's "port town" since the river and the estuary did not allow larger ships to enter. Here there could be up to 100 larger and smaller ships at a time and heavy traffic. The steamships that went along the coast called at Kleven and not Mandal itself. Several shipyards were responsible for the maintenance of ships that had gained speed during the voyage from Scotland, Denmark or the Baltic Sea area. In addition, the ships' needs ensured a great deal of activity with trade, agricultural goods, accommodation and inns.

Along the river towards Mandal, a shipyard was established for the construction and maintenance of smaller ships, sawmills, trading houses, a reeper railway and many smaller craft businesses that provided services to the town. Shipping created the basis for commercial activities that took advantage of the opportunities offered by the import of raw materials and the shipping of finished products. Norway had large imports of oil products, especially kerosene for lamps. Imports are estimated at approximately 1.2 million liters in 1850 and represented a market with great growth potential. The kerosene came mainly from Bathgate in Scotland and was extracted from coal according to a method invented by the chemist James Young and put into production from about 1845.

«From Risøbank» Foto: Amaldus Nielsen / Nasjonalgalleriet

«From Risøbank» Foto: Amaldus Nielsen / Nasjonalgalleriet

The Salvesen family

The Napoleonic wars and the great economic decline during and after them had largely removed the old great families and the new era created new dominant families based on economic progress, more than background and nobility. Skilled, enterprising people gained access to capital and invested widely in shipping, sawmilling, trade and created new fortunes based on Mandal's growth and trade with the Baltic Sea, Denmark, the Netherlands and Great Britain. Mandal had an extremely limited upper class, but perhaps up to 300 people in the "middle class" with assets over NOK 800.

One of the leading families was the Salvesen dynasty. They could trace their ancestry back to the 18th century and had experienced both great success and spectacular decline during the Napoleonic Wars with a blockade against Norway, but managed to establish themselves again in Mandal with Thomas Salvesen as head of the family. He ran the family's businesses with parties in shipping, shipbroking, timber, sawmilling, exporting ice and trading with Mandal's uplands, but also Denmark, the Baltic Sea, Germany and especially Scotland. His six sons received a solid education, practice in their own company and long stays with trading partners in Germany, Poland and Scotland.

Eldest son, Edvard, was trained as a doctor at the University of Christiania. Son no. 2, Carl Emil Salvesen, was trained as a lawyer, and had to take care of the family's interests in Mandal when his father, Thomas Salvesen, died. The family established i.a. a large sawmill based on the use of steam engines as a power source at the outlet of the Mandal river. Son no. 3, Henrik, worked in the family's companies in Mandal, but unfortunately died early in 1848. Son no. 4, Theodor Salvesen, was educated in several places, including in Kønigsberg and Pilau. He traveled to Glasgow to learn British trade and language, but quickly chose to settle in Leith / Grangemouth instead from 1843. It was a smaller place, well located for trade and shipping to Scandinavia, Germany and the Baltic and it was possible for a enterprising young man to establish his own trading house. Theodor established the firm J.T.Salvesen & Co and worked this up into a solid business with holdings in shipping, mines and trade. Then his younger brother, Christian, came to Leith via Stettin, and 5 years in his father's business in Mandal. He worked up his own business in collaboration with local investors and shipping companies. The main partner was George Turnbull and the firm was named Turnbull, Salvesen & Co, (T.S&Co) Leith, Scotland.

England and the Netherlands' repeal of the Navigation Act, priority for their own country's ships, and emphasis on free trade created an expanded basis for shipping and trade via Norwegian ships with skilled and cheap crew. The business idea was to own parties in many different ships for which one then acted as a broker. The Salvesen family's establishment on both sides of the North Sea created the basis for exploiting the import/export opportunities from both sides. The family transported iron, coal and probably some kerosene to Norway, Germany and the Baltic Sea area and brought back timber, fish, grain and agricultural products. This was a highly competitive business with many uncertain moments and high risk, not least with the loss of ships. Eventually, the family managed to get the public contract for the establishment and replenishment of Norway's coal reserves along the entire coast of Norway. These warehouses were necessary to supply the increasing traffic of steamships that carried goods, mail and passengers along the coast from Vadsø to Christiania. This gave the Salvesen companies a network of trade representatives and the basis for tramp ships and later liner shipping along the entire coast of Norway. Scottish business got a boost when Christian Salvesen became vice-consul for the Electorate of Hanover. He thus became a broker for large parts of the freight in Germany and increased the company's income. The company T.S. & Co nevertheless struggled continuously with weak finances.

In the 1840s, James Young had developed a chemical refining process in which he could extract oil products from coal with a high content of bitumen. Young obtained patents for this process around every potential market in the world and made a fortune. His success created an investment fever in Scotland for coal mining and oil production. Christian Salvesen also wanted to join the adventure, and he brought his brother Theodor along.

The challenge was that Norway had tariffs on the import of oil products and Young's patents blocked the possibility of refining himself and getting to the very source of the wealth. But the Salvesen brothers discovered that Young had not taken out his patent in Norway and there was no duty on the import of coal. There was an opportunity to establish a refinery in Norway based on coal from Scotland. They already had shipping to Norway with coal, well-established family contacts in Mandal that could be the basis for the investment in Norway, access to capital and sufficient courage to invest in promising opportunities. In addition, Christian had bet hard for many years without being entirely successful. The company was afloat thanks to the plaster brokerage business and unquenchable internal loyalty between the brothers, but that was nothing more either. The brothers were willing to bet on something that could become a very good business if they succeeded.

Establishment of a refinery at Risøbank near Mandal

Carl Emil was partly reluctantly appointed to run the family business in Mandal. He was the link the brothers in Scotland needed to get started. In the new year 1862, the "Paraffin Oil Company of Mandal" was established with 20,000 pounds in share capital and Carl Emil Salvesen as manager of operations in Norway. The money came from Theodor Salvesen and George Turnbull, brother of Carl Emil's wife. The first activity was to buy a large area of land just outside the city, Risøbank, for 1,000 speciedals (NOK 4,000). This was a considerable amount and a good deal for Tønnes Wattne, who in this way got rid of some large blown sand plains, knolls and various useless sandy beaches.

But for a refinery the site was eminently suitable. It had easy access for large ships, a safe harbor in the Bankefjord, plenty of space for buildings, large equipment and a short distance to Mandal with craft businesses and cheap labour. The first project was to build a combined breakwater and jetty so that building materials could be brought ashore. The jetty inland was built in stone with a wooden jetty built on stilts. The facility was so large and solid that several boats could be moored at the same time. The dock was so solid that parts are still standing, and all shipping for 10 years passed through this facility. Runways were built for barrels so that unloading and loading went quickly.

First report about a kerosene factory at Mandal.

First report about a kerosene factory at Mandal.

Foto: Lister og Mandals Amtstidende, 12.4.1862 / Risøbank Interkommunalt Selskap.

Most of the technical equipment for the refinery was bought used in Scotland and transported over with the company's ship "Roe". Turnbull and Salvesen had secured James Young's technical expert and operations manager at Bathgate, John Galletly, as technical manager for the plant. He had contacts and knowledge that made it possible to get the right equipment cheap and used in Scotland and more importantly how to rebuild it at Risøbank so that a refinery actually worked.

All resources in the parent companies were mobilized to find used equipment, reduce costs and sell parts in ships to raise financing. Galletly sailed with the first of three loads on 1 April 1862 and the plant was put into operation in September of the same year. It testifies to almost superhuman abilities and willingness to realize the project from the management in Scotland and Mandal. It must have been a big boost for the business community and craftsmen in Mandal to erect a facility of more than 20 buildings with docks and equipment within 6 months.

The production line was set up as close a copy of the Bathgate plant as possible and approximately 120 liters of kerosene were purchased from Young to carry out accurate analyzes of the finished product. Galletly and his contacts in Scotland arranged the delivery of chemicals for the refining process, lamps, production equipment and 12 Scottish specialists to assist in the construction and lead the Norwegian workers.

An example of creativity was how to import barrels for the first production. To avoid customs duties on the barrels, they were filled with coal and imported as packaging duty-free. Production started after 5 months and revealed a number of weaknesses. Parts of the production line did not work satisfactorily and much had to be adjusted and modified in Mandal. The first production did not meet Young's quality and the sales team had to use kerosene from Young for demonstrations of the lamps' quality along the coast. However, the problems were quickly resolved and the quality not only improved, but actually became better than James Young's products from Bathgate.

Construction at the refinery

Besides the breakwater and wharf, more than 20 buildings with specialized purposes were built in 1862. The largest was the building that contained 8 built-in "retorts" or "boilers" where the coal was "boiled" so that the oil products were released for further distillation. Since then, more buildings were added so that the total number of retorts reached 26. One building housed the "vitriol or lead chamber" where sulfuric acid was produced for use in the refining process with a lead storage tank that held up to 530m3 of liquid, 19 x 5.6 meters and 5 meters high. There was a coal house for storing and crushing the coal, a separate cooper's workshop where barrels were made and maintained for transporting the finished products, and an engine house that housed the steam engines that produced power for the entire plant. Storage tanks for finished products were dug into the ground, pipe streets, two large storage tanks by the wharf and a bottling plant for bottling into barrels. The largest tanks could be up to 5 meters in diameter. The various steps in the refining process had their own buildings, forges, workshops and warehouses also required their own buildings.

Map of the facility with piers and runways for barrels.

Map of the facility with piers and runways for barrels.

Foto: Ulf Aanonsen/ Risøbank Interkommunalt Selskap

The administration building was small but nice with a hipped roof slightly extended from the refinery. Since then, the refinery director and the foreign workers were given housing just outside the refinery area, and these buildings are still standing. A total of 24 new buildings were erected up to 1866 with a total insured value of approx. 15,000 special dalers or NOK 60,000. The insurance only covered the buildings, not machines and other equipment inside the houses. It was a very expensive and large project by the standards of the time, with around 50 buildings including the residential buildings.

Mandal Støperi was established together with the sawmill at Kastellodden at the bottom of Mandalselva. Here they cast lamp bases, tools and parts for the refinery. Both the foundry and the sawmill were owned by the Salvesen family. The foundry built its own house just outside the fence of the refinery by the sea where the parts for finished lamps were put together. Burners, glass and containers were imported from Scotland. Gradually, glass was bought from Hadeland Glassverk and Christiania Glass. Kerosene was in large parts of Norway a new product and without oil lamps there was no one to sell the kerosene to. The "Lampefabrikken" produced and sold more than 110,000 lamps during the refinery's lifetime. In addition to this production, Høvik Staal also supplied oil lamps throughout the country.

Kerosene lamp from Mandal Støperi circa 1864.

Kerosene lamp from Mandal Støperi circa 1864.

Foto: Ulf Aanonsen / Risøbank Interkommunalt Selskap

Initially, large parts of the potential customer circle had not seen oil lamps. Consequently, cheap lamps had to be produced, as well as advertising and training in how the lamps worked; storage of kerosene, filling, the lighting process, maintenance of the candle wick and how to extinguish them. Gradually the products became known and so cheap that many could buy both lamps and kerosene, even though many could not afford to have the light on every night. Most homes in Norway had been relegated to daylight and the light from the hearth or a cypress twig, and a kerosene lamp in the home was a change we can hardly imagine today. One could actually read, write and work after dark.

Refining and process

After commissioning, the refinery received approximately 160 tonnes of coal from Bathgate in Scotland each week. Bathgate was only about 30 km from Leith and the coal was transported on the company's ships. The coal was "Boghead" or "Cannel-coal", which contained up to 30% more bitumen (the actual oil) than ordinary coal. The coal was broken down into lumps that could not be larger than 4-7 cm in the coal house, transported by trolley with used rails from Salvesen's mine in Scotland and loaded into tall cast iron cylinders, the "retorts", almost like huge pressure cookers. There were four retorts per furnace. Here, the coal was heated with ordinary wood and coke heating so that liquid evaporated and was collected in various pipes which were again cooled with cold water. The secreted liquid was dark brown and was collected in a brick tank for crude oil, the "black liquor hole". The remaining coal had almost turned into coke and could be used for fuel in the ovens or filling material at the plant.

The crude oil was then pumped into boilers, "stills", for further heating and evaporation/distillation. Cooling again took place by the liquid being led via pipes through water tanks to a new collection tank, the "stirringhouse". Here various chemicals were added to the liquid, oil of vitriol (sulphuric acid), sodium nitrate, soda etc., which separated tar and ammonium sulphate. This was drained. The remaining oil then underwent further multi-phase distillation which separated Naphtha, paraffin oil for lamps, turpentine and the residual product which solidified to a solid consistency on cooling.

Naphtha was used for lighting at the refinery and sold as an additive in paints and varnishes. The kerosene was refined further until it acquired a clear color and became almost odorless. There were two qualities; completely clear or slightly darker where completely clear was the finest and most expensive. The products had a good reputation for being almost odorless, barely there and gave a clear, nice light without too much soot formation on the lamp lenses. This kerosene had a slightly higher specific gravity than competing foreign products and that made it a little more difficult to use. The residual product was pressed so that oil flowed out, and was sold as lubricating oil and grease. The final residual product was pitch, which in reality was only stored and then used as a foundation in the narrow roads to the refinery area. Bek still lies in the ground at Risøbank just a few cm below the top layer of grass and plants.

In the first years, the refining process was kept going around the clock with around 120 men working daily. It is stated in 1866 that 9,400 barrels of kerosene and 500 barrels of machine oil (lubricating oil) were produced. If we assume that these are standard barrels, then they contained 163 liters each (English standard 1865) or a total of about 1.5 million liters of kerosene and 80,000 liters of lubricating oil. This was a large production over almost 4 years, but still only a part of the total consumption in Norway. The best quality kerosene achieved a price of 18 shillings or about 59 øre per litre. It would later turn out that this price was far too high in the competition with imported kerosene, where prices could drop all the way down to 10 to 14 øre per litre.

From 1862 to 1866, 60 tonnes of paraffin wax were also made as a by-product of the paraffin refining itself. Normally, you would make ordinary candles from this, but the company wanted to teach people to use oil lamps and did not want a competing product in its own range, so it was sold on to other manufacturers. The by-products coal tar and turpentine were sold on to farmers and fishermen for use on buildings and boats.

The production of sulfuric acid was extensive, perhaps as much as 5-6 tonnes a week. Here, much was used in own production and nothing was sold as sulfuric acid. But some acid was recovered in production and mixed with bone meal and, together with ammonium sulphate, this was sold as artificial fertilizer for agriculture under the name "Superphosphate". This "artificial fertiliser" was recommended by the Agricultural College at Ås and the production was probably around 200 tonnes a year. The products from the refinery were good and achieved, among other things, the highest award at the Stockholm exhibition in 1866 for kerosene, lubricating oil, naphtha, sulfuric acid and grease.

The kerosene was transported in barrels and the end consumer had to buy the quantity she wanted, and make sure she had a jug with her for shipping and storage. At first there were complaints that the kerosene was sooty and smelly, but this subsided as people learned to maintain their lamps with proper lighting and use. Incidentally, it was considered particularly dirty work to clean kerosene lamps, and in better-off houses you could have many of them, table lamps, steel lamps, ceiling lamps with lifting devices, wall lamps, lamps with colored glass, portable lanterns, etc. A round burner is originally a kerosene lamp with circular wick. In most households, people were content with a lamp and were very happy to be able to use and maintain it.

Parafin Oil Company of Mandal, 1863.

Parafin Oil Company of Mandal, 1863.

Foto: Odd Arne Nomedal, Fotofabrikken Mandal / Risøbank Interkommunalt Selskap.

The workers and their importance to Mandal

There were 80 to 150 workers at the refinery in the initial phase 1862 – 1866. Few of these used the title kerosene worker. Most were various types of craftsmen who kept their professional titles such as blacksmith, cooper, carpenter, bricklayer, etc. They could also work for other than the refinery. Some were recruited directly from Mandal's population, but the refinery was a dangerous, dirty and windy place of work so the town's population preferred other work. The solution was immigration from the villages around Mandal, mainly Kvinnesdal, Lyngdal and Åseral. The workers were paid from NOK 1.70 to NOK 2 a day. This was the usual moderate salary for a worker in Mandal, but well paid for householders from Agder's mountain villages who had hardly been paid in money before. Many were able to raise their families first in rented rooms and later build their own houses. They settled in the new district "Støkkan" and then in the district "Sanden", which was built as more space was needed. These districts were partly referred to as "Lille Kvinnesdal". The population in Mandal increased by around 1,000 people from 1855 to 1865, largely due to the job opportunities at the refinery and increased activity by purchasing services in Mandal. People lived close together and what we see today as small houses could have 20 to 30 residents with up to 6 families.

The refinery also needed quite a few experienced specialist workers. These came from refineries in Scotland and brought with them knowledge from there. This applied to the operations managers, engineers and also some of the refinery workers with specialist knowledge of the refining processes. In total, it may have involved up to 15 people, some with families. They lived in a residential building just outside the refinery area itself under cramped and unappealing conditions.

There were few safety measures beyond individual caution and cooperation with colleagues. We must assume that there was a strong smell and partly also of dangerous gas in the air. The many ovens and boilers easily caused burns. The chemical reactions were not yet understood so that there were often smaller explosions that affected the hearing and were also dangerous in themselves. It was particularly dangerous to open boilers with still hot products so that the gas from the oil came into contact with cold air, and there are reports of minor explosions with personal injuries. The tanks had to be cleaned without an oxygen supply, and a man was watching and had the cleaner pulled out when he passed out. The facility was located at a safe distance from the city and in addition, a trench was dug for the collection of leaked products around the entire facility. High winds dispersed the potentially dangerous gas most days.

In reality, Mandal had no street lighting beyond four oil lamps, but with the refinery so to speak on the neighboring plot, 30 street lamps fired with kerosene were invested in. Mandal must have been the first, or one of the first, cities in Norway with such street lighting. The city's combined firemen and police constables performed the solemn cleaning of the windows and lighting at fixed times every evening and extinguishing before midnight. The refinery also made generous contributions to various public celebrations and celebrations in Mandal. The union with Sweden, 17 May and other events were celebrated with colored lanterns, light trellises from the Mandal to the refinery and large colored flares.

The refinery became a small tourist attraction as you could take a day trip from Kristiansand by steamboat, food and drink and a tour of the refinery on certain Sundays.

Major unforeseen problems in 1866

The refinery operated largely according to plans from 1862 to 1866. But the expected financial earnings did not materialize. The production itself stuck to the plans in terms of volume and few major cost overruns. But they did not achieve the planned prices or a sufficient volume of sales around Norway or exports outside Norway. Competition from cheaper Scottish products was fierce and the prospect of massive imports from the US threatened. It was so bad that at the end of 1865 there was an inventory calculated at 10,000 pounds (about 50,000 Spd) and some of the investors in Scotland wanted to shut down the refinery.

Refinery director Carl Emil Salvesen's house just outside the refinery, Furulunden, Mandal.

Refinery director Carl Emil Salvesen's house just outside the refinery, Furulunden, Mandal.

Foto: Ulf Aanonsen / Risøbank Interkommunalt Selskap.

The house well illustrates the sobriety in spending that characterized all parts of the operation.

Originally, the director had a direct view of the facility at Risøbank.

The trees planted after the refinery closed did not exist in 1862.

Carl Emil Salvesen was the refinery's reluctant top manager and probably struggled with competence, language and motivation. John Galletly and his Scottish colleagues did an excellent job at the refinery and the cooperation seems to have been good despite the fact that communication with the Norwegian-speaking workers was difficult. Eventually the locals learned Scottish oil vocabulary, (perhaps not unlike the development in Stavanger 100 years later). But unfortunately it turned out that Galletly had provided himself with at least an extra £50 in the coffers, and he was replaced with Charles Irvine from Scotland. He was professionally skilled, but the collaboration with Carl Emil and the Norwegian staff did not go well. It went so far that the owners in Scotland had to put him in his place and point out that it was Carl Emil and not him who ran the refinery. The ownership probably kept it going out of respect for the aging and ill Theodor Salvesen.

The financial main man behind the refinery was Theodor Salvesen, although Christian may have been the original initiator. Theodor had contributed the most capital, obtained partners, financed his brother Carl Emil, formally owned 50% of the shares and really believed in the refinery's possibilities. When he died at Christmas 1865, the entire project had to be reassessed along with a number of other negative factors. James Young's patents in Scotland and the world expired, and there began a violent expansion in Scottish production of kerosene from coal with falling prices. The battle for the coal and overproduction meant that it became difficult to obtain raw material for Mandal and the price competition tore away the basis for the refinery's original production. The Norwegian Creditbank was the main bank connection and they felt that their claims had to be paid or get solid guarantees for lending. Initially, Teodor's estate provided the guarantees and the estate's shares were sold fairly to Christian Salvesen and George Turnbull, but that was not enough in itself to secure the business.

In early 1866, operations were temporarily suspended and most of the workers lost their jobs. The entire company was reorganized under the new name "Caledonian Oil Company" and George Turnbull injected new capital together with Christian Salvesen. Carl Emil Salvesen did not have the opportunity to contribute capital. In addition, a number of Scottish investors joined the partnership and production at the refinery resumed. The Scottish investors were interested in selling their coal and their local Scottish oil production to Norway. But production at the refinery in Mandal had to be rescheduled. Instead of coal, crude oil was now imported from Scotland and refining continued based on this. As a result, there was no use for the retorts and production was considerably simplified with far fewer workers. In the period 1867 to May 1869, 2.4 million liters of crude oil were imported to the refinery for further processing and sale in Norway.

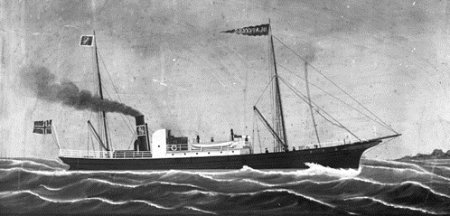

D/S Nedenes, D/S Olav Kyrre and D/S Risøbank - The world's first tanker for mineral oil?

In 1864, the Salvesen family bought the first steamship registered in Mandal. It was 68 registered tonnes and was named D/S Nedenes. One of the ship's purposes was to transport oil products from the refinery to trading posts along the coast. Unfortunately, the ship was already wrecked in 1866 outside Farsund and shipping had to be arranged via other ships that went along the Norwegian coast. This was unsatisfactory since shipping became irregular and trading places and consumers did not receive their products as promised and expected. From August 1867, D/S Olav Kyrre of 213 registered tons took over much of the freight for the refinery. Both boats had their own cargo spaces for the refinery's products, perhaps mostly because of the risk of leaks and possible destruction of other cargo. D/S Olav Kyrre was made in Newcastle and sailed for a full 70 years.

From 1866, crude oil came in barrels to the refinery together with coal to fire the refinery's boilers on sailing ships from Scotland. This was a dangerous and inefficient transport. The round barrels made poor use of the ships' cargo capacity and were prone to leaking and causing loss of cargo and problems for the ship. In the summer of 1867, the partners met to find a better shipping method. Then one of the partners, MacKelvie, suggested that a ship could be built that used the same principle as the railway, namely freight in specially made tanks mounted in the ship like tank wagons on the railway.

«D/S Olaf Kyrre».

«D/S Olaf Kyrre».

Foto: Risøbank Interkommunalt Selskap

Construction began in the spring of 1868 in Inverkeithing of an iron ship of 186 register tons with specially made tanks mounted in the ship. Own tanks reduced the possibility of leaks and in effect made the ship double-bottomed. Full oil tanks also functioned as ballast, although it had not been understood that the tanks had to be divided into smaller compartments to avoid large movements with weight displacement in bad weather. A steam pump was mounted on deck to be able to load and unload the tanks quickly and efficiently. In total, the ship could take up to 400 tonnes of cargo, including the crude oil, divided into two holds. A deck was made over the tanks so that dry cargo could be transported there. Sailing with dry cargo required that there was also cargo in the tanks to ensure the ship's stability. The ship was named "D/S Risøbank", was fully rigged and had a stack discharge on 16 September 1868. The ship's first cargo was from Leith on 11 November 1868 and this made Risøbank one of the world's first ships specially built for the transport of oil in tankers.

Risøbank transported crude oil and coal to the refinery in Mandal and took various freight back to Scotland under the leadership of Captain Edmund Eeg from Mandal. A main product was "pit props" made i.a. at the Salvesen family's sawmill in Mandal. Pit props were pre-cut wooden poles (standard size) that were used directly in the mines in Great Britain to support the mine shafts in the country's many mines. The demand for them was very high at good prices. The tank caps were designed so that pit props could be loaded into the tanks as return cargo from Norway to Scotland. Agder had a large production of staves for barrels. Scotland and England had a great need for this product, and Risøbank probably also shipped this. Risøbank also had a few trips along the Norwegian coast and delivered coal and picked up lumber in return.

On its 9th trip on 30 September 1869, Risøbank ran aground off Scotland. The crew of five and two passengers were rescued by the Scottish Coastguard and the ship was later successfully salvaged and brought back to the shipyard in Inverkeithing partly based on the buoyancy of empty barrels in the cargo. It had extensive damage and a total of 54 plates had to be replaced along with 30 frames and further sealing of the hull. Additional tanks were also installed. The ship was put into normal operation again in February 1870, carrying crude oil and coal to the refinery.

Artistic rendering of "Risøbank" based on the description of the ship.

Artistic rendering of "Risøbank" based on the description of the ship.

Foto: Risøbank Interkommunalt Selskap

By December 1870, the refinery was almost out of crude oil and needed supplies. Usually the ships did not sail this dangerous route in winter, but Risøbank nevertheless took on board 200 barrels of oil and 201 tons of coal in Newcastle on 19 January 1871. The company must have been in a difficult situation to push through such a risky trip and Risøbank unfortunately went down with the entire crew of six and cargo on the trip back to Mandal. There has been speculation about several reasons, i.a. that the cargo shifted in bad weather, that the oil in the unsectioned tanks shifted the weight balance in the ship in high waves or that you sailed on ice floes in the very cold winter. Rumors arose that other sailors had seen people on ice floes off the coast. Remains of the cargo were later found outside Denmark.

Unfortunately, it is not known what happened, but the result of the sinking was that the company had lost its supply line and the profitability of the refinery did not allow the construction of new oil tanks. Christian Salvesen in Scotland was forced to write to his older brother, Carl Emil: "We have noted that the facility has ceased. It is best that you now reduce the workforce as best you can. With the loss of Risøbank, there is no longer any possibility of making the oil factory profitable. We therefore believe that as many as possible of the workers must be notified of dismissal." Thus, the final period for the refinery was set.

In reality, the basis for operation at the refinery was long gone. Scottish producers refined the oil more cheaply and Carl Emil had to sell his own oil at a loss to get sales. Production in the USA rose sharply and their products were even cheaper and were soon to compete with Scottish oil as well. In addition, the Norwegian authorities changed the tax policy in 1869 so that the refinery in Mandal lost all protection. Taxes on crude oil were removed and taxes on refined oil were greatly reduced. The investment in "Risøbank" and the perseverance of the Salvesen family must be understood in terms of loyalty to Mandal, more than the business acumen and ability for flexibility the family showed in other parts of its business.

The legacy of The Oil Paraffin Company of Mandal

Carl Emil ended operations at Risøbank and retired to the management of the family's businesses in Mandal; sawmill, foundry and shipping. The kerosene factory was left with a few thousand unsold oil lamps, and these were sold as far as possible. Christian Salvesen bought the rest of the estate for 750 pounds and together they realized what was possible by selling machinery, equipment, building materials, the wooden pier and everything that could be removed and sold. But in total, it was calculated that the partnership behind the refinery lost perhaps up to 35,000 pounds on the investment in the entire period from 1862 to 1871. Fortunately, the Salvesen family had other legs to stand on and the company in Scotland continued with very good results in the timber trade from Norway and Finland, cellulose, mining, whaling and shipping. The company is still alive and is one of Great Britain's largest transport and forwarding companies today.

Christian transferred the property in Mandal to his son Lord Edward Salvesen in 1895. Carl Emil had started planting between the refinery area and Mandal to stop the sand escaping early. used for foundations for roads in Furulunden. Mass was added to cover the wounds after the plant and the planting greatly expanded. For almost 100 years, the area has been a magnificent walk and recreation area for Mandal's population. The lord himself had an English-inspired wooden mansion with a tenant's residence, outbuildings, park and orangery in the part of Furulunden that today is simply called "The Lord". All building work was carried out by a local builder with local labour.

“The Lord” at Risøbank and Mandal.

“The Lord” at Risøbank and Mandal.

The Salvesen family had this beautiful property built

as his "residence" for long stays in the city, especially in the summer.

Operations at the refinery had been significantly reduced in the period up to 1871 and it seems that most of the workers had found other work in Mandal's small but expanding business, sawmilling, shipyards and shipping. Some of the workers with families had already emigrated to America in 1868 with the Mandals and the Salvesen family's own emigrant ship, Præciosa. The Præciosa had a very difficult crossing and on top of it all it ran aground and sank in the entrance to Quebec in the St. Lawrence Channel in Canada. All were saved, but there is no information on how much the emigrants lost in the sinking. In any case, it is a frightening picture of how small margins people lived under 150 years ago.

For Mandal, the districts of Støkkan and Sanden remain as monuments to the great immigration of the 1860s, and the houses show that many families got a start and a roof over their heads in the city. Mandal largely avoided the violent decline experienced by many coastal towns in Norway during the global economic crisis in the mid-1870s. The town's many small businesses were flexible and the shipping business went well for Mandal. The Salvesen family remained faithful supporters and maintained their business in the town. A striking paradox is that the Mandal Oil Paraffin Company, together with the import of Scottish kerosene, created a market for lamp oil and other oil products in Norway. The last remaining taxes and duties on kerosene were removed in 1890, parallel to the establishment of Standard Oil in Norway. This company went almost to the table and established a monopoly which provided the basis for a very good business for two or three generations under the name Esso.

The Risøbank refinery area appears today as a great open air area.

The Risøbank refinery area appears today as a great open air area.

Foto: Odd Arne Nomedal, Fotofabrikken Mandal / Risøbank Interkommunalt Selskap

Sources and literature:

Ulf Aanensen, Risøbank Interkommunal Selskap and Mandal Historielag, has put a lot of work into preserving and making the history of Risøbank, the Salvesen family and "the Paraffin Oil Company of Mandal" known. He has been very helpful during the preparation of this article.

Slekters gang, no. 1, 2018, Mandal Historielag, The paraffin factory at Risøbank and its tanker "Risøbank", Ulf Aanensen. The Salvesen of Leith, Wray Wamplew, Scottish Academic Press, Edinburgh and London, 1975

Støkkan - An outland becomes a district, Yngvar Lillesund, Fritjof Salvesen Bok og Offsettrykkeri, Mandal 1989.

Agder's History 1840 – 1920, Bjørn Slettan, Kristiansand 1998

Illustrated Newspaper no. 8, 1864, "The paraffin oil factory at Mandal"

Lindesnes 13.9.1923, "The petroleum industry in its infancy, the kerosene factory at Risøbank".

Lindesnes 21.6.1940, "The kerosene factory at Risøbank in the 1860s", Arthur W. Nielsen.

Volund 1980, Norwegian Technical Museum, Norway's first oil refinery, Mandal Parafin Olie Co, 1862 – 1874, Olav Wetting.

Norwegian Maritime Museum 1988, Schooner "Risøbank" Norway's first iron sailing ship and tanker?, Arthur Weyergang-Nielsen.

From Sea and Land 3, From Mandal to Scotland, Arthur Weyergang-Nielsen, Fritjof Salvesen Book and Offset Printing, Mandal 1992

An industrial city is emerging : 1850-1950, Bjørn Slettan, Mandal Municipality, Mandal 2006